Reviews of She, Self-Winding

October 30, 2022

Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry asserts the feminine self within time. The poet winds her own clock. She, Self-Winding, the title of her fourth collection, reflects the tensions between public and private, tradition and renewal, past and present, hardcore pragmatism and poignant romanticism. It also reflects on history, and histories, of war and immigration.

The narrative compression, mysterious wording, and dramatic irony in Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry remind you of fractured fairytales, blues ballads, tragic novels with tongue-in-cheek endings, and all those moody, pregnant moments in the films of Wong Kar-wai.

Lưu Diệu Vân’s poems are about women submitting to, or ambiguously subverting, their narratives. The poems are both tragic and comic. Camp mixed with pathos. For example, “My Stepmother’s Shoes” is about a woman who crosses an entire ocean to join her lover who lives in a cold climate, bringing with her a suitcase full of summer shoes. She later finds out that this lover is only “a sweet talker/[who] didn’t even have a bank account.” But the Cinderella ending comes years later, with a twist. In her seventies, this stepmother finds herself “handcuffed” to happiness and won’t leave her bed! The word handcuffed is disturbingly cheeky —is she toying with the reader’s expectations of a happy feminist ending, or is she saying that enslavement becomes liberation when submitted willingly in an S&M context? We will never know, because we still exist in a world stranded between shame and fulfillment, silence and indecision. This world, while offering many advancements for women, still is full of taboos, still imposes rules and regulations on their bodies, in both the public and private realms.

The push-pull between tradition and progress, weakness and strength, is the liveliest, most incisive aspect of Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry. In “Premier Funeral,” while a Vietnamese grandfather is enlightened enough to confer upon his beloved granddaughter the radical “privilege of the first-born, absent son,” he however succumbs to a seemingly inevitable and most cliché of endings. The grandfather’s death, by opium addiction, is the typical fate befallen many Confucian intellectuals. While a common Vietnamese woman’s destiny is to take care of her family, an educated Vietnamese man’s freedom is simply his ability to escape both private and public responsibilities.

There is no real assimilation for a cultural transplant, as her fractured experience has turned her into Frankenstein’s monster. The romance celebrated in Hollywood classic films, of well-scrubbed teenagers hot-rodding down antiseptic American streets while classic rock blaring on the radio, becomes a domestic horror tableau in Lưu Diệu Vân’s poem, something that could have been captured by the photographer Diane Arbus. In “Scent-Free Speed,” an Asian father, “bitter of warfare and cesspit cleanup,” guns a Mustang Thunderbird through dilapidated neighborhoods while heaping verbal abuse on his family. His teenage daughter, “late in menstruating,” is desperate to be an adult. Lost in her private romance inspired by a cosmetic perfume ad, yet also trapped in the horrendous present, the girl feels drenched by the summer heat and rashy from dime store fishnet stockings.

Despite Lưu Diệu Vân’s frequent use of humor and irony, there is also a deep romanticism in her poetry, reminding you of the three tenets of love—faith, hope, and charity, celebrated in Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians. Let’s all hear the very moving closure of her poem, “Of Dust and Us”:

My hand gives you uncontaminated confidence to hold yourself accountable

flashes to ashes

The country house with see-through ceiling reappears to the south

Where my vagrant body always points

And yours, fearlessly near.

To read Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry, is to see “through a glass, darkly; but then face to face.”

Đinh Từ Bích Thúy

Đinh Từ Bích Thúy is the coeditor of the Vietnamese literary magazine Da Màu, editor-at-large for Asymptote Journal, freelance critic, and literary translator. She was a 2020 writer-in-resident at Woodlawn-Pope Leighey House in Alexandria, Virginia, and a 2018 scholar at the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference in Vermont. Her works have appeared in NPR, NBC, Da Màu, Asymptote, Prairie Schooner, Manoa, Michigan Quarterly Review, Rain Taxi Review of Books, among others. She is based in the Washington DC Metropolitan Area, USA.

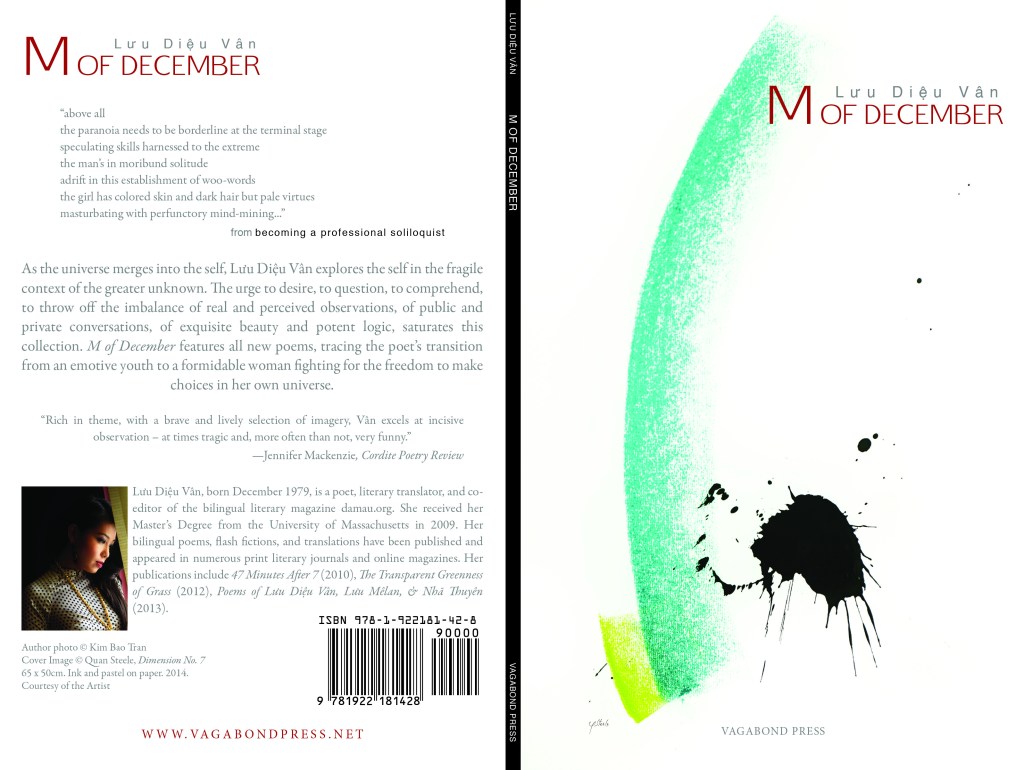

Jennifer Mackenzie Reviews Lưu Diệu Vân’s M of December

Reading M of December is rather like going to a spectacular exhibition at a gallery where images of all kind swirl, proclaim, collide and re-form – the viewer takes the opportunity of a brief leave to attempt to come up with a coherent response. Having gone into this gallery, and exited on a number of occasions, what I have come up with is a response to the formed fragmentation of its individual poems, travelling through discordancy via the robust vigour of forceful lines and sharp elisions.

In the first section of the collection, ‘December’, individual poems read as constructed assemblages with dazzling juxtapositions of imagery. In ‘B.C. bees’, perception is presented as molten, contested, as chthonically and chronologically unsettled:

the fire has eyes that glide through lies beyond B.C. and cunning centuries the sage offers secrets to the universe seeing is a plague the distance between heaven and death is a U turn

The artist at work then makes a selection process by constructing a verbal installation:

each century’s special promotion written in the DNA of people making headlines the telling bees dash for the wedlocked bedrock like thumbtacks on a topsoil cork board sucking out stories as big as Vesuvius’ pumice mortality preserves in conceding hives

This sense of poem as installation, or constructed artefact, is also on display in ‘micro exhibition’, where images of the artefact and that of the natural world play off each other, reflecting both boldness and uncertainty – wonderment in the faith of what the poet has created. The poem starts out with a strong image:

a religious artefact stands imposingly, sanctimoniously reflecting the recondite sea beneath

The imposing nature of the image could be seen to conflate into the act of perception itself:

the glass incrustation patiently collects black and white stones of uncertainty, downplays the six senses, magnifies the perception

This culminates in the final verse, where the act of writing itself presents ambivalently:

on top of the mountain lays a hesitating temple of ink, half wanting to leap, half keeping hold of subsistence

Essentially, Vân works herself out of hesitation; boldly placing the natural and the constructed to achieve a momentary interlocking of effect.

In ‘imaginary holy friend’, the robust somehow distils itself into an evocation of lyric, socially sanctioned violence. Here, the gendered de-formations of ‘people playing god’ merge into a joint reflection of the abused body and nature, with the short lines being particularly effec-tive:

god frolicking people elongated neck binding people playing god moon-blade foot binding slippers stumped by lotus ponds punctured meat of the bony flute meshes pain filtered cries hair side-parted slope of decisiveness gossamer crease hidden in plain terrain mountain goiter of the soil lake urethra of the deep volcano mouth of the inflamed smoke lung of the unsung a favourite blacksmith of mortal parts to play Operation with in the bedridden darkness

The poem ‘inside an armoured chrysalis’ pursues the vision of metaphysical clash in its expressionistic and apocalyptic tableau of war:

the cloak of war rips open like a caterpillar’s final grip on innocence seas of poppies barrage from rising towers

Its imagery is strong and confrontational, for instance: ‘stench of fresh fir’, ‘molecules of gassed up bodies’ and ‘thinning polyskies of barebones and sulking skulls’. The delicacy (and the shorter line) seen in ‘imaginary holy friend’ effectively returns in the final two lines, playing out the metamorphic import of ‘chrysalis and caterpillar’:

the rest of us frantically disperse in search of a butterfly that can cry

The section, ‘December’, continues with an enthralling juxtaposition of imagery from nature, the world of objects, and the body, all morphing into each other in unexpected combinations. ‘coiling forest’ presents a take on the Cinderella story, of ‘tales of a princess always needing rescues / of a prince.’ Vân portrays a set in motion, in which ‘a vanishing forest [is] coiling into itself’ and ‘doors are pushing upwardly silently within the forest like wild / mushrooms.’ The poet abruptly segues from this protean vision, into savage reflection:

Cinderella never made it that last second of the forest’s final new year’s eve when no one can own sadness but merely takes care of it for the next victim in line

In a similar vein, ‘melancholia of caramel afternoons’ moves from the mythical to the contemporary with spectacular elision:

nirvana the night’s cologne caging in missing hinges from its macho wings on the wall of memory Sabrina arrives through the urgent ringtone

The second section of the collection, ‘M’ is akin to work seen in Poems of Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan & Nhã Thuyên (Vagabond Press, 2013), extending Vân’s poetry both in theme and imagery, nailing the acerbic line. ‘to a younger poet self’ and ‘naïve writer’ respectively look back in sardonic reappraisal: of, firstly, an early love affair; and, secondly, of early flurries onto the literary circuit. In ‘to a younger poet self’, the ‘Big Heartbreak’ is framed with literary reference:

all your twenty-two self-pities a fatal infatuation for Rumi and e.e.cummings insomnias yet of age jolts of maiden pain love smog tints grays of verses laments vicariously postaged to Neruda

Its references morph into an effectively crafted take on writing and the body:

you shatter into creation the feminist phoenix way riding in the dark on the biro’s horn rendering poisoned sensations savable chastity’s optional to tame metaphors you jump through a needle’s eye avoiding the thread’s pull

‘naïve writer’ also sees the collection open itself up to some narrative savagery. In Vân’s view, literary PR appears as the selling of self, where ‘the writer’s skin must be as thick as their copious flows of / topless appearance on the fictional bed’, this ‘literary reception / bed, on which not a single space is deserted’, from which the speaker is suddenly excluded, ‘forever trapped outside’.

‘M’ explores the evolving world of feminist critique, drawing on history, culture and patriarchy, putting the poet’s skills at dramatic scene-setting to good effect. ‘feminine reconciliation’ reads as a pithy riff on popular magazines and their penchant for advice columns: ;what a woman wants is shoes that go with every mood / what she needs is an attitude that can wear many hats.’ In ‘the bindi escape’, a living deity leaves ritual behind:

12 days of purifying in isolation she wipes the red sun belated dreams off her charcoal-rimmed eyes the spirit vacates the body light escaping between her remoistenable thighs two entities lie languidly in the corona of midnight innocence making bolts out of peepal with burgeoning tongues the bindi’s making a scandalous cross towards freedom

In ‘here comes the truth’ the rituals of a traditional upbringing are laid waste by sudden flight at the end of the Vietnam War, when the refrain of ‘White Christmas’ signalled the urgency to evacuate:

she was not privy to the monk’s staged self-immolation White Christmas and Bing Crosby’s common key the entire village fumbling in the red land

The poem concludes with an epiphany of arrival in the United States, where the speaker ‘got all the answers from the immaculate self-cleaning airport toilets / no P. M. of W. C. forcing a tip from her.’

‘my would be sister’ reflects on this flight, and the alternative histories it represents. Growing up as ‘an au fait young woman’, she sees her home country as a place where ‘female laborers’ [sic] take ‘routine / beatings from their husbands like cultural norms.’ However, ‘if the night-sea escape had failed’ she might be, at 15, ‘prime age for pre-arranged marriage, lying leisurely on the hammock in the coconut grove.’

Another particularly strong poem in the collection, ‘on the 7thfloor’ skillfully employs the trope of a movie shot to suggest dark emotions within a contained and eroticised space – the theatre of the room:

the ceiling fan’s blades decapitate the plump moon of the 7th floor flashes of light contaminate the eerie air absolute silence spirit possessed with an obvious sixth sense a woman plunging a needle through each fingernail sewing a secret lover’s name on the inside of her longing thighs without uttering a cry

Although issues of gender predominate in the second section of the collection, it is not an exclusive preoccupation. Among poems of a different timbre and subject, ‘the cloud hunter’ is a delightful, witty response to pareidoia, as the poem transforms from observations of cultural predilections: ‘the Vietnamese see a pixy dragon / the Chinese see a bad omen’, to being a somewhat rueful celebration of poetry:

I am proud of my trade regardless protecting the hangover of our fading faction there are so few of us left surviving barely on the illicitly traded puff of time and in order to avoid detection we now call ourselves poets

Overall, this lively and impressive collection showcases feminist humour shaping the sharp cut of the poetic line. It sees Lưu Diệu Vân extending her range, and presenting a number of compelling poems, which invite rewarding re-reading.

Jennifer Mackenzie

Jennifer Mackenzie is a poet and reviewer, focusing on writing from and about the Asian region. Her most recent work is Navigable Ink (Transit Lounge 2020) which she presented in 2023 at the Ubud Writers Festival and at the Mathrubhumi Festival of Literary Arts in Trivandrum.

Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan & Nhã Thuyên: Into The Gate of Imagination

by Trịnh Y Thư, poet

It is quite an inspirational surprise to see a beautiful book of poetry, in which not one, not two, but three Vietnamese female poets concurrently share their creative arts. Of course, I’m talking about the project immaculately undertaken by a group of authors and translators, Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese, to bring forth a volume of poetry written by Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan and Nhã Thuyên, the three emerging poets whose names have become increasingly familiar with poetry lovers inside Viet Nam and abroad.

It is quite an inspirational surprise to see a beautiful book of poetry, in which not one, not two, but three Vietnamese female poets concurrently share their creative arts. Of course, I’m talking about the project immaculately undertaken by a group of authors and translators, Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese, to bring forth a volume of poetry written by Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan and Nhã Thuyên, the three emerging poets whose names have become increasingly familiar with poetry lovers inside Viet Nam and abroad.

…..

Lưu Diệu Vân, the reluctant non-conformist

You can say Lưu Diệu Vân’s poems are interesting because of her skillful and exquisite usage of imagery. In fact, it’s a tour-de-force. In almost every single poem, one could find an intriguing effect created by the peculiar choice of words that she inserts at the right place and the right time. The lyrics are song-like but abstract, a rather strange combination, thus, emitting the mystics that can be attributed to the feeling of uncertainty. There is nothing absolute here. Nothing is definitive. Nothing is consummate. The inner self is examined within the precarious surrounding for she is quite self-conscious about the relationships, not only between interconnecting individuals but also between individual and his/her environment.

………

Jennifer Mackenzie Reviews Asia Pacific Writing Series Books 1-4

Jennifer Mackenzie

Jennifer Mackenzie is the author of Borobudur (Transit Lounge, 2009), republished in Indonesia as Borobudur and Other Poems (Lontar, 2012) and has been busy promoting it at festivals and conferences in Asia. She is now working on a number of projects, including an exploration of poetry and dance, ‘Map/Feet’. Her participation in the Irrawaddy Festival was supported by a writer’s travel grant from the Australia Council for the Arts.

Jennifer Mackenzie is the author of Borobudur (Transit Lounge, 2009), republished in Indonesia as Borobudur and Other Poems (Lontar, 2012) and has been busy promoting it at festivals and conferences in Asia. She is now working on a number of projects, including an exploration of poetry and dance, ‘Map/Feet’. Her participation in the Irrawaddy Festival was supported by a writer’s travel grant from the Australia Council for the Arts.

Vagabond Press has recently issued four attractively presented volumes of poetry from the Asia Pacific region. Each contains the work of three poets and represents China, Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines, respectively.

……

Moving from the aesthetics in ‘The Chagall and Leaf’, a world defined by the beauty of image and sound, we enter into a different world, a contemporary world full of noise, turmoil and extempore choice. My first reaction to the poetry of Lưu Diệu Vân (b.1979) in the selection from Vietnam was that I wanted to hear her read live:

ask a poem to a bar

leave it alone

sit at a distant table

watch its every move

while intoxicated

take another poem home (Lưu Diệu Vân, ‘time killers for poets’)

Rich in theme, with a brave and lively selection of imagery, Vân excels at incisive observation – at times tragic, and more often than not, very funny. The poem ‘post-feminism’, coming after a crisp dissection of Confucianism in ‘dead philosopher’s apologia’, is a highlight. Here are some snippets from this tale of an unfortunate dinner-date:

he eagerly criticizes, after a few inhales of thick smoke

you have yet to possess true feminine traits…

I wear red high heels, clingy off-shoulder silk dress, and

elegant white pearls …

I widen my eyes in surprise and yawn discreetly with my

mouth covered, slowly cross my long legs, neatly fold

both hands on my lap, calmly interrupt his second

criticism after asking the waiter to bring me a separate

bill for the lemonade and crème brûlée to take home …

Feminist and political appraisal is strengthened by Vân’s awareness of neighbourhood, specifically its imagery in such poems as ‘dolls and bicycles’ and ‘the finality of peace’. This location of politics in the individual’s life is evident in ‘my 1975 story’, through a transposition of time that presents national tragedy in two short, vivid pages:

I am a young woman, approaching eighteen years of age

scrambling around the square, morning, noon, day and night

where they bind prisoners to flagpoles

under the broiling sun

imploring gazes

offering to exchange wedding bands and keepsakes for half a

sandwich

and a mouthful of cold water

……

Jennifer Mackenzie Reviews Asia Pacific Writing Series Books 1-4

Poems of Lưu Diệu Vân, Lưu Mêlan & Nhã Thuyên – Series Introduction Essay

Nguyen Tien Hoang, poet

…….

The three poets featured in this volume were born in the postwar period, their writings emerged when the set political agenda had already been gone, the old tracks of writing with an eye for the publication authority had been removed. These however are less important than the fact that their writings demand new ways of reading. The heightened language, the hidden pathos and the discernible passions may be the meeting ground for the intersecting flights, yet each poem sets its own pace, tilts its rudder in different way and brings the readers to different points of unexpectedness. The diversity of their concerns and subject matters apparently reflect the social and environmental challenges they are facing. Their responses are above all in the language itself.

…….

Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry appeals for reason and rationality, it defies the customary tendency that looks into poetry for the assuaging effects. Like the modern poets of the generation before her (Bishop, Sexton and Plath), she considers being a woman is a centrally important fact as much as writing poetry is concerned. Her poetic persona embodies the feminist traits of a modern woman who takes on the world as it is: a field of experiences. The poem is the result of thought-process and rational reflections along the traversing-paths of interactions between the writer, who is conscious of the contemporary milieu she is in, and the outside world. A poem is a voice that names, delineates and redefines, and mediates. Lưu Diệu Vân’s poetry has a strong emphasis on diction, it employs a language which address the public. Her poetry is not for the page alone, it is also for the tongue, for the performance stage. It is a spoken voice, the audience will hear the wit of the words, the exuberance of the vernacular and the energy of the speech.

Leave a comment